- Foreword

- Proposals Process

- 200x Membership

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Terms, notation, and references

- 3 Usage requirements

- 4 Documentation requirements

- 5 Compliance and labeling

- 6 Glossary

- 7 The optional Block word set

- 8 The optional Double-Number word set

- 9 The optional Exception word set

- 10 The optional Facility word set

- 11 The optional File-Access word set

- 12 The optional Floating-Point word set

- 13 The optional Locals word set

- 14 The optional Memory-Allocation word set

- 15 The optional Programming-Tools word set

- 16 The optional Search-Order word set

- 17 The optional String word set

- 18 The optional Extended-Character word set

- Annex A: Rationale

- Annex B: Bibliography

- Annex C: Compatibility analysis

- Annex D: Portability guide

- Annex E: Reference Implementations

- Annex F: Test Suite

- Annex H: Alphabetic list of words

Annex A: Rationale

A.1 Introduction

A.1.1 Purpose

A.1.2 Scope

When judging relative merits of proposed changes to the standard, the members of the committee were guided by the following goals (listed in alphabetic order):

| Consistency | The standard provides a functionally complete set of words with minimal functional overlap. |

| Cost of compliance | This goal includes such issues as common practice, how much existing code would be broken by the proposed change, and the amount of effort required to bring existing applications and systems into conformity with the standard. |

| Efficiency | Execution speed, memory compactness. |

| Portability | Words chosen for inclusion should be free of system-dependent features. |

| Readability | Forth definition names should clearly delineate their behavior. That behavior should have an apparent simplicity which supports rapid understanding. Forth should be easily taught and support readily maintained code. |

| Utility | Be judged to have sufficiently essential functionality and frequency of use to be deemed suitable for inclusion. |

A.2 Terms and notation

A.2.1 Definitions of terms

- aligned

-

Data can only be loaded from and stored to addresses that are aligned

according to the alignment requirements of the accessed type. Field

offsets that are added to structure addresses also need to be aligned.

- ambiguous condition

-

The response of a Standard System to an ambiguous condition is left

to the discretion of the implementor. A Standard System need not

explicitly detect or report the occurrence of ambiguous conditions.

- cross compiler

-

Cross compilers may be used to prepare a program for execution in an

embedded system, or may be used to generate Forth kernels either for

the same or a different run-time environment.

- data field

-

In earlier standards, data fields were known as "parameter fields".

On subroutine threaded Forth systems, everything is object code. There are no traditional code or data fields. Only a word defined by CREATE or by a word that calls CREATE has a data field. Only a data field defined via CREATE can be manipulated portably.

- word set

-

This standard recognizes that some functions, while useful in certain

application areas, are not sufficiently general to justify requiring

them in all Forth systems. Further, it is helpful to group Forth

words according to related functions. These issues are dealt with

using the concept of word sets.

The "Core" word set contains the essential body of words in a Forth system. It is the only "required" word set. Other word sets defined in this standard are optional additions to make it possible to provide Standard Systems with tailored levels of functionality.

A.2.2 Notation

A.2.2.2 Stack notation

The use of -sys, orig, and dest data types in stack effect diagrams conveys two pieces of information. First, it warns the reader that many implementations use the data stack in unspecified ways for those purposes, so that items underneath on either the control-flow or data stacks are unavailable. Second, in cases where orig and dest are used, explicit pairing rules are documented on the assumption that all systems will implement that model so that its results are equivalent to employment of some stack, and that in fact many implementations do use the data stack for this purpose. However, nothing in this standard requires that implementations actually employ the data stack (or any other) for this purpose so long as the implied behavior of the model is maintained.

A.3 Usage requirements

Forth systems are unusually simple to develop, in comparison with compilers for more conventional languages such as C. In addition to Forth systems supported by vendors, public-domain implementations and implementation guides have been widely available for nearly twenty years, and a large number of individuals have developed their own Forth systems. As a result, a variety of implementation approaches have developed, each optimized for a particular platform or target market.The committee has endeavored to accommodate this diversity by constraining implementors as little as possible, consistent with a goal of defining a standard interface between an underlying Forth System and an application program being developed on it.

Similarly, we will not undertake in this section to tell you how to implement a Forth System, but rather will provide some guidance as to what the minimum requirements are for systems that can properly claim compliance with this standard.

A.3.1 Data types

Most computers deal with arbitrary bit patterns. There is no way to determine by inspection whether a cell contains an address or an unsigned integer. The only meaning a datum possesses is the meaning assigned by an application.

When data are operated upon, the meaning of the result depends on the meaning assigned to the input values. Some combinations of input values produce meaningless results: for instance, what meaning can be assigned to the arithmetic sum of the ASCII representation of the character "A" and a TRUE flag? The answer may be "no meaning"; or alternatively, that operation might be the first step in producing a checksum. Context is the determiner.

The discipline of circumscribing meaning which a program may assign to various combinations of bit patterns is sometimes called data typing. Many computer languages impose explicit data typing and have compilers that prevent ill-defined operations.

Forth rarely explicitly imposes data-type restrictions. Still, data types implicitly do exist, and discipline is required, particularly if portability of programs is a goal. In Forth, it is incumbent upon the programmer (rather than the compiler) to determine that data are accurately typed.

This section attempts to offer guidance regarding de facto data typing in Forth.

A.3.1.2 Character types

The correct identification and proper manipulation of the character data type is beyond the purview of Forth's enforcement of data type by means of stack depth. Characters do not necessarily occupy the entire width of their single stack entry with meaningful data. While the distinction between signed and unsigned character is entirely absent from the formal specification of Forth, the tendency in practice is to treat characters as short positive integers when mathematical operations come into play.

- Standard Character Set

- The storage unit for the character data type

(C@, C!, FILL, etc.)

must be able to contain unsigned numbers from 0 through 255.

- An implementation is not required to restrict character

storage to that range, but a Standard Program without

environmental dependencies cannot assume the ability to

store numbers outside that range in a "char" location.

- The allowed number representations are two's-complement,

one's-complement, and signed-magnitude. Note that all of

these number systems agree on the representation of positive

numbers.

- Since a "char" can store small positive numbers

and since the character data type is a sub-range of the

unsigned integer data type, C! must store the n

least-significant bits of a cell (8 <= n <= bits/cell).

Given the enumeration of allowed number representations and

their known encodings, "TRUE

xxC!xxC@" must leave a stack item with some number of bits set, which will thus will be accepted as non-zero by IF. - For the purposes of input (KEY, ACCEPT, etc.)

and output (EMIT, TYPE, etc.), the encoding

between numbers and human-readable symbols is ISO646/IRV

(ASCII) within the range from 32 to 126 (space to ~).

EBCDIC is out (most "EBCDIC" computer systems support ASCII

too). Outside that range, it is up to the implementation. The

obvious implementation choice is to use ASCII control

characters for the range from 0 to 31, at least for the

"displayable" characters in that range (TAB, RETURN, LINEFEED,

FORMFEED). However, this is not as clear-cut as it may seem,

because of the variation between operating systems on the

treatment of those characters. For example, some systems TAB

to 4 character boundaries, others to 8 character boundaries,

and others to preset tab stops. Some systems perform an automatic

linefeed after a carriage return, others perform an automatic

carriage return after a linefeed, and others do neither.

The codes from 128 to 255 may eventually be standardized, either formally or informally, for use as international characters, such as the letters with diacritical marks found in many European languages. One such encoding is the 8-bit ISO Latin-1 character set. The computer marketplace at large will eventually decide which encoding set of those characters prevails. For Forth implementations running under an operating system (the majority of those running on standard platforms these days), most Forth implementors will probably choose to do whatever the system does, without performing any remapping within the domain of the Forth system itself.

- A Standard Program can depend on the ability to receive

any character in the range 32 ... 126 through KEY,

and similarly to display the same set of characters with

EMIT. If a program must be able to receive or display

any particular character outside that range, it can declare

an environmental dependency on the ability to receive or

display that character.

- A Standard Program cannot use control characters in

definition names. However, a Standard System is not required

to enforce this prohibition. Thus, existing systems that

currently allow control characters in words names from

BLOCK source may continue to allow them, and

programs running on those systems will continue to work. In

text file source, the parsing action with space as a

delimiter (e.g., BL WORD) treats control

characters the same as spaces. This effectively implies that

you cannot use control characters in definition names from

text-file source, since the text interpreter will treat the

control characters as delimiters. Note that this

"control-character folding" applies only when space is the

delimiter, thus the phrase "CHAR

)WORD" may collect a string containing control characters.

- The storage unit for the character data type

(C@, C!, FILL, etc.)

must be able to contain unsigned numbers from 0 through 255.

- Storage and retrieval

Characters are transferred from the data stack to memory by C! and from memory to the data stack by C@. A number of lower-significance bits equivalent to the implementation-dependent width of a character are transferred from a popped data stack entry to an address by the action of C! without affecting any bits which may comprise the higher-significance portion of the cell at the destination address; however, the action of C@ clears all higher-significance bits of the data stack entry which it pushes that are beyond the implementation-dependent width of a character (which may include implementation-defined display information in the higher-significance bits). The programmer should keep in mind that operating upon arbitrary stack entries with words intended for the character data type may result in truncation of such data.

- Manipulation on the stack

In addition to C@ and C!, characters are moved to, from and upon the data stack by the following words:

- Additional operations

The following mathematical operators are valid for character data:

The following comparison and bitwise operators may be valid for characters, keeping in mind that display information cached in the most significant bits of characters in an implementation-defined fashion may have to be masked or otherwise dealt with:

A.3.1.3 Single-cell types

A single-cell stack entry viewed without regard to typing is the fundamental data type of Forth. All other data types are actually represented by one or more single-cell stack entries.

- Storage and retrieval

Single-cell data are transferred from the stack to memory by !; from memory to the stack by @. All bits are transferred in both directions and no type checking of any sort is performed, nor does the Standard System check that a memory address used by ! or @ is properly aligned or properly sized to hold the datum thus transferred.

- Manipulation on the stack

Here is a selection of the most important words which move single-cell data to, from and upon the data stack:

- Comparison operators

The following comparison operators are universally valid for one or more single cells:

A.3.1.3.1 Flags

A FALSE flag is a single-cell datum with all bits unset, and a TRUE flag is a single-cell datum with all bits set. While Forth words which test flags accept any non-null bit pattern as true, there exists the concept of the well-formed flag. If an operation whose result is to be used as a flag may produce any bit-mask other than TRUE or FALSE, the recommended discipline is to convert the result to a well-formed flag by means of the Forth word 0<> so that the result of any subsequent logical operations on the flag will be predictable.In addition to the words which move, fetch and store single-cell items, the following words are valid for operations on one or more flag data residing on the data stack:

A.3.1.3.2 Integers

A single-cell datum may be treated by a Standard Program as a signed integer. Moving and storing such data is performed as for any single-cell data. In addition to the universally-applicable operators for single-cell data specified above, the following mathematical and comparison operators are valid for single-cell signed integers:

Given the same number of bits, unsigned integers usually represent twice the number of absolute values representable by signed integers.

A single-cell datum may be treated by a Standard Program as an unsigned integer. Moving and storing such data is performed as for any single-cell data. In addition, the following mathematical and comparison operators are valid for single-cell unsigned integers:

A.3.1.3.3 Addresses

An address is uniquely represented as a single cell unsigned number and can be treated as such when being moved to, from, or upon the stack. Conversely, each unsigned number represents a unique address (which is not necessarily an address of accessible memory). This one-to-one relationship between addresses and unsigned numbers forces an equivalence between address arithmetic and the corresponding operations on unsigned numbers.Several operators are provided specifically for address arithmetic:

and, if the floating-point word set is present:

A Standard Program may never assume a particular correspondence between a Forth address and the physical address to which it is mapped.

A.3.1.3.4 Counted strings

Forth 94 moved toward the consistent use of the "c-addr u" representation of strings on the stack. The use of the alternate "address of counted string" stack representation is discouraged. The traditional Forth words WORD and FIND continue to use the "address of counted string" representation for historical reasons. The new word C", added as a porting aid for existing programs, also uses the counted string representation.

Counted strings remain useful as a way to store strings in memory. This use is not discouraged, but when references to such strings appear on the stack, it is preferable to use the "c-addr u" representation.

A.3.1.3.5 Execution tokens

The association between an execution token and a definition is static. Once made, it does not change with changes in the search order or anything else. However it may not be unique, e.g., the phrases

might return the same value.

A.3.1.3.6 Error results

The term ior was originally defined to describe the result of an input/output operation. This was extended to include other operations.

A.3.1.4 Cell-pair types

- Storage and retrieval

Two operators are provided to fetch and store cell pairs:

- Manipulation on the stack

Additionally, these operators may be used to move cell pairs from, to and upon the stack:

- Comparison

The following comparison operations are universally valid for cell pairs:

A.3.1.4.1 Double-Cell Integers

If a double-cell integer is to be treated as signed, the following comparison and mathematical operations are valid:

If a double-cell integer is to be treated as unsigned, the following comparison and mathematical operations are valid:

A.3.1.4.2 Character strings

See: A.3.1.3.4 Counted strings.

A.3.2 The Implementation environment

A.3.2.1 Numbers

Traditionally, Forth has been implemented on two's-complement machines where there is a one-to-one mapping of signed numbers to unsigned numbers — any single cell item can be viewed either as a signed or unsigned number. Indeed, the signed representation of any positive number is identical to the equivalent unsigned representation. Further, addresses are treated as unsigned numbers: there is no distinct pointer type. Arithmetic ordering on two's complement machines allows + and - to work on both signed and unsigned numbers. This arithmetic behavior is deeply embedded in common Forth practice.As a consequence of these behaviors, the likely ranges of signed and unsigned numbers for implementations hosted on each of the permissible arithmetic architectures is:

| Arithmetic architecture | signed numbers | unsigned numbers | |||||

| Two's complement | -n-1 | to | n | 0 | to | 2n+1 | |

| One's complement | -n | to | n | 0 | to | n | |

| Signed magnitude | -n | to | n | 0 | to | n | |

where n is the largest positive signed number. For all three architectures, signed numbers in the 0 to n range are bitwise identical to the corresponding unsigned number. Note that unsigned numbers on a signed magnitude machine are equivalent to signed non-negative numbers as a consequence of the forced correspondence between addresses and unsigned numbers and of the required behavior of + and -.

For reference, these number representations may be defined by the way that NEGATE is implemented:

| two's complement: | : NEGATE INVERT 1+ ; |

| one's complement: | : NEGATE INVERT ; |

| signed-magnitude: | : NEGATE HIGH-BIT XOR ;

|

where HIGH-BIT is a bit mask with only the most-significant

bit set. Note that all of these number systems agree on the

representation of non-negative numbers.

Per 3.2.1.1 Internal number representation and 6.1.0270 0=, the implementor must ensure that no standard or supported word return negative zero for any numeric (non-Boolean or flag) result. Many existing programmer assumptions will be violated otherwise.

There is no requirement to implement circular unsigned arithmetic, nor to set the range of unsigned numbers to the full size of a cell. There is historical precedent for limiting the range of u to that of +n, which is permissible when the cell size is greater than 16 bits.

A.3.2.1.2 Digit conversion

For example, an implementation might convert the characters "a" through "z" identically to the characters "A" through "Z", or it might treat the characters " [ " through " " as additional digits with decimal values 36 through 71, respectively.

A.3.2.2 Arithmetic

A.3.2.2.1 Integer division

The Forth-79 Standard specifies that the signed division operators (/, /MOD, MOD, */MOD, and */) round non-integer quotients towards zero (symmetric division). Forth 83 changed the semantics of these operators to round towards negative infinity (floored division). Some in the Forth community have declined to convert systems and applications from the Forth-79 to the Forth-83 divide. To resolve this issue, a Forth-2012 system is permitted to supply either floored or symmetric operators. In addition, a standard system must provide a floored division primitive (FM/MOD), a symmetric division primitive (SM/REM), and a mixed precision multiplication operator (M*).This compromise protects the investment made in current Forth applications; Forth-79 and Forth-83 programs are automatically compliant with Forth 94 with respect to division. In practice, the rounding direction rarely matters to applications. However, if a program requires a specific rounding direction, it can use the floored division primitive FM/MOD or the symmetric division primitive SM/REM to construct a division operator of the desired flavor. This simple technique can be used to convert Forth-79 and Forth-83 programs to Forth 94 without any analysis of the original programs.

A.3.2.2.2 Other integer operations

Whether underflow occurs depends on the data-type of the result. For example, the phrase1 2 - underflows if the result is

unsigned and produces the valid signed result -1.

A.3.2.3 Stacks

The only data type in Forth which has concrete rather than abstract existence is the stack entry. Even this primitive typing Forth only enforces by the hard reality of stack underflow or overflow. The programmer must have a clear idea of the number of stack entries to be consumed by the execution of a word and the number of entries that will be pushed back to a stack by the execution of a word. The observation of anomalous occurrences on the data stack is the first line of defense whereby the programmer may recognize errors in an application program. It is also worth remembering that multiple stack errors caused by erroneous application code are frequently of equal and opposite magnitude, causing complementary (and deceptive) results.For these reasons and a host of other reasons, the one unambiguous, uncontroversial, and indispensable programming discipline observed since the earliest days of Forth is that of providing a stack diagram for all additions to the application dictionary with the exception of static constructs such as VARIABLEs and CONSTANTs.

A.3.2.3.2 Control-flow stack

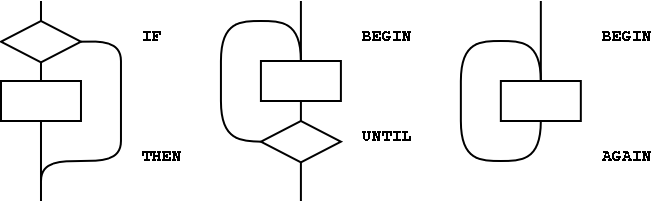

The simplest use of control-flow words is to implement the basic control structures shown in figure A.1.

In control flow every branch, or transfer of control, must terminate at some destination. A natural implementation uses a stack to remember the origin of forward branches and the destination of backward branches. At a minimum, only the location of each origin or destination must be indicated, although other implementation-dependent information also may be maintained.

An origin is the location of the branch itself. A destination is where control would continue if the branch were taken. A destination is needed to resolve the branch address for each origin, and conversely, if every control-flow path is completed no unused destinations can remain.

With the addition of just three words (AHEAD, CS-ROLL and CS-PICK), the basic control-flow words supply the primitives necessary to compile a variety of transportable control structures. The abilities required are compilation of forward and backward conditional and unconditional branches and compile-time management of branch origins and destinations. Table A.1 shows the desired behavior.

| at compile-time, | |||

| word: | supplies: | resolves: | is used to: |

| IF | orig | mark origin of forward conditional branch | |

| THEN | orig | resolve IF or AHEAD | |

| BEGIN | dest | mark backward destination | |

| AGAIN | dest | resolve with backward unconditional branch | |

| UNTIL | dest | resolve with backward conditional branch | |

| AHEAD | orig | mark origin of forward unconditional branch | |

| CS-PICK | copy item on control-flow stack | ||

| CS-ROLL | reorder items on control-flow stack | ||

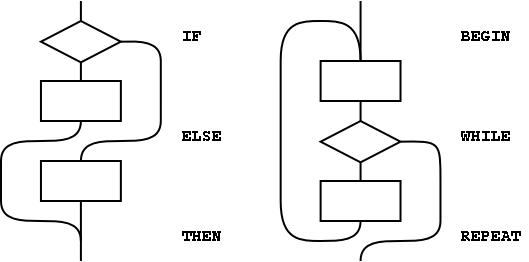

With these tools, the remaining basic control-structure elements, shown in figure A.2, can be defined. The stack notation used here for immediate words is ( compilation / execution ).

\ conditional exit from loops

POSTPONE IF \ conditional forward brach

1 CS-ROLL \ keep dest on top

; IMMEDIATE

: REPEAT ( orig dest -- / -- )

\ resolve a single WHILE and return to BEGIN

POSTPONE AGAIN \ uncond. backward branch to dest

POSTPONE THEN \ resolve forward branch from orig

; IMMEDIATE

: ELSE ( orig1 -- orig2 / -- )

\ resolve IF supplying alternate execution

POSTPONE AHEAD \ unconditional forward branch orig2

1 CS-ROLL \ put orig1 back on top

POSTPONE THEN \ resolve forward branch from orig1

; IMMEDIATE

Forth control flow provides a solution for well-known problems with strictly structured programming.

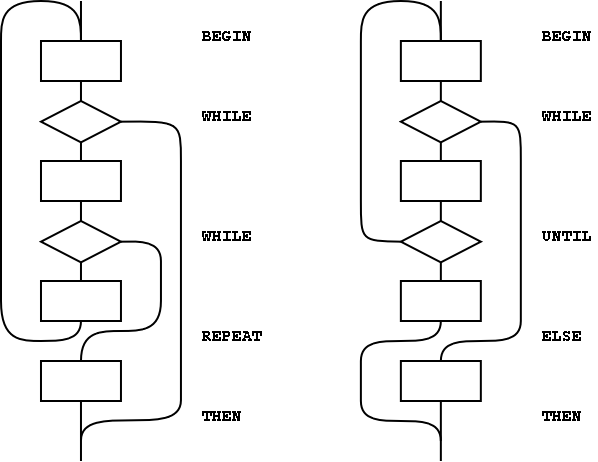

The basic control structures can be supplemented, as shown in the examples in figure A.3, with additional WHILEs in BEGIN ... UNTIL and BEGIN ... WHILE ... REPEAT structures. However, for each additional WHILE there must be a THEN at the end of the structure. THEN completes the syntax with WHILE and indicates where to continue execution when the WHILE transfers control. The use of more than one additional WHILE is possible but not common. Note that if the user finds this use of THEN undesirable, an alias with a more likable name could be defined.

Additional actions may be performed between the control flow word (the REPEAT or UNTIL) and the THEN that matches the additional WHILE. Further, if additional actions are desired for normal termination and early termination, the alternative actions may be separated by the ordinary Forth ELSE. The termination actions are all specified after the body of the loop.

Note that REPEAT creates an anomaly when matching the

WHILE with ELSE or THEN, most notably when

compared with the BEGIN...UNTIL case. That is,

there will be one less ELSE or THEN than there are

WHILEs because REPEAT resolves one THEN. As

above, if the user finds this count mismatch undesirable, REPEAT

could be replaced in-line by its own definition.

Other loop-exit control-flow words, and even other loops, can be defined. The only requirements are that the control-flow stack is properly maintained and manipulated.

The simple implementation of the CASE structure below is an example of control structure extension. Note the maintenance of the data stack to prevent interference with the possible control-flow stack usage.

: OF ( #of -- orig #of+1 / x -- )

1+ ( count OFs )

>R ( move off the stack in case the control-flow )

( stack is the data stack. )

POSTPONE OVER POSTPONE = ( copy and test case value)

POSTPONE IF ( add orig to control flow stack )

POSTPONE DROP ( discards case value if = )

R> ( we can bring count back now )

; IMMEDIATE

: ENDOF ( orig1 #of -- orig2 #of )

>R ( move off the stack in case the control-flow )

( stack is the data stack. )

POSTPONE ELSE

R> ( we can bring count back now )

; IMMEDIATE

: ENDCASE ( orig1..orign #of -- )

POSTPONE DROP ( discard case value )

0 ?DO

POSTPONE THEN

LOOP

; IMMEDIATE

A.3.2.3.3 Return stack

The restrictions in section 3.2.3.3 Return stack are necessary if implementations are to be allowed to place loop parameters on the return stack.

A.3.2.6 Environmental queries

The size in address units of various data types may be determined by phrases such as1 CHARS. Similarly, alignment may be

determined by phrases such as 1 ALIGNED.

The environmental queries are divided into two groups: those that

always produce the same value and those that might not. The former

groups include entries such as MAX-N. This information is

fixed by the hardware or by the design of the Forth system; a user

is guaranteed that asking the question once is sufficient.

The other, now obsolescent, group of queries are for things that may legitimately change over time. For example an application might test for the presence of the Double Number word set using an environment query. If it is missing, the system could invoke a system-dependent process to load the word set. The system is permitted to change ENVIRONMENT?'s database so that subsequent queries about it indicate that it is present.

Note that a query that returns an "unknown" response could produce a "known" result on a subsequent query.

A.3.2.7 Obsolescent Environmental Queries

When reviewing the Forth 94 Standard, the question of adapting the word set queries had to be addressed. Despite the recommendation in Forth 94, word set queries have not been supported in a meaningful way by many systems. Consequently, these queries are not used by many programmers. The committee was unwilling to exacerbate the problem by introducing additional queries for the revised word sets. The committee has therefore declared the word set environment queries (see table 3.5) as obsolescent with the intention of removing them altogether in the next revision. They are retained in this standard to support existing Forth 94 programs. New programs should not use them.

A.3.2.8 Extension queries

A.3.3 The Forth dictionary

A Standard Program may redefine a standard word with a non-standard definition. The program is still standard (since it can be built on any Standard System), but the effect is to make the combined entity (Standard System plus Standard Program) a non-standard system.

A.3.3.1 Name space

A.3.3.1.2 Definition names

The language in this section is there to ensure the portability of Standard Programs. If a program uses something outside the Standard that it does not provide itself, there is no guarantee that another implementation will have what the program needs to run. There is no intent whatsoever to imply that all Forth programs will be somehow lacking or inferior because they are not standard; some of the finest jewels of the programmer's art will be non-standard. At the same time, the committee is trying to ensure that a program labeled "Standard" will meet certain expectations, particularly with regard to portability.In many system environments the input source is unable to supply certain non-graphic characters due to external factors, such as the use of those characters for flow control or editing. In addition, when interpreting from a text file, the parsing function specifically treats non-graphic characters like spaces; thus words received by the text interpreter will not contain embedded non-graphic characters. To allow implementations in such environments to call themselves standard, this minor restriction on Standard Programs is necessary.

A Standard System is allowed to permit the creation of definition names containing non-graphic characters. Historically, such names were used for keyboard editing functions and "invisible" words.

A.3.3.2 Code space

A.3.3.3 Data space

The words >IN, BASE, BLK, SCR, SOURCE, SOURCE-ID, STATE contain information used by the Forth system in its operation and may be of use to the application. Any assumption made by the application about data available in the Forth system it did not store other than the data just listed is an environmental dependency.

There is no point in specifying (in the Standard) both what is and what is not addressable. A Standard Program may NOT address:

- Directly into the data or return stacks;

- Into a definition's data field if not stored by the application.

The read-only restrictions arise because some Forth systems run from ROM and some share I/O buffers with other users or systems. Portable programs cannot know which areas are affected, hence the general restrictions.

A.3.3.3.1 Address alignment

Some processors have restrictions on the addresses that can be used by memory access instructions. For example, some architectures require 16-bit data to be loaded or stored only at even addresses and 32-bit data only at addresses that are multiples of four.

An implementor can handle these alignment restrictions in one of two ways. Forth's memory access words (@, !, +!, etc.) could be implemented in terms of smaller-width access instructions, which have no alignment restrictions. For example, on a system with 16-bit cells, @ could be implemented with two byte-fetch instructions and a reassembly of the bytes into a 16-bit cell. Although this conceals hardware restrictions from the programmer, it is inefficient, and may have unintended side effects in some hardware environments. An alternate implementation could define each memory-access word using the native instructions that most closely match the word's function. The 16-bit cell system could implement @ using the processor's 16-bit fetch instruction, in this case, the responsibility for giving @ a correctly-aligned address falls on the programmer. A portable program must assume that alignment may be required and follow the requirements of this section.

A.3.3.3.2 Contiguous regions

The data space of a Forth system comes in discontiguous regions. The location of some regions is provided by the system, some by the program. Data space is contiguous within regions, allowing address arithmetic to generate valid addresses only within a single region. A Standard Program cannot make any assumptions about the relative placement of multiple regions in memory.

Section 3.3.3.2 does prescribe conditions under which contiguous regions of data space may be obtained. For example:

makes a table whose address is returned by TABLE. In

accessing this table,

TABLE C@ | will return 1 |

TABLE CHAR+ C@ | will return 2 |

TABLE 2 CHARS +

ALIGNED @ | will return 1000 |

TABLE 2 CHARS +

ALIGNED CELL+ @ | will return 2000. |

Similarly,

makes an array 1000 address units in size. A more portable strategy would define the array in application units, such as:

This array can be indexed like this:

A.3.3.3.6 Other transient regions

In many existing Forth systems, these areas are at HERE or just beyond it, hence the many restrictions.(2*n)+2 is the size of a character string containing the unpunctuated binary representation of the maximum double number with a leading minus sign and a trailing space.

Implementation note: Since the minimum value of n is 16, the absolute minimum size of the pictured numeric output string is 34 characters. But if your implementation has a larger n, you must also increase the size of the pictured numeric output string.

A.3.4 The Forth text interpreter

A.3.4.3 Semantics

The "initiation semantics" correspond to the code that is executed upon entering a definition, analogous to the code executed by EXIT upon leaving a definition. The "run-time semantics" correspond to code fragments, such as literals or branches, that are compiled inside colon definitions by words with explicit compilation semantics.In a Forth cross compiler, the execution semantics may be specified to occur in the host system only, the target system only, or in both systems. For example, it may be appropriate for words such as CELLS to execute on the host system returning a value describing the target, for colon definitions to execute only on the target, and for CONSTANT and VARIABLE to have execution behaviors on both systems. Details of cross compiler behavior are beyond the scope of this standard.

A.3.4.3.2 Interpretation semantics

For a variety of reasons, this standard does not define interpretation semantics for every word. Examples of these words are >R, .", DO, and IF. Nothing in this Standard precludes an implementation from providing interpretation semantics for these words, such as interactive control-flow words. However, a Standard Program may not use them in interpretation state.

A.3.4.5 Compilation

Compiler recursion at the definition level consumes excessive resources, especially to support locals. The committee does not believe that the benefits justify the costs. Nesting definitions is also not common practice and won't work on many systems.

A.4 Documentation requirements

A.4.1 System documentation

A.4.2 Program documentation

A.5 Compliance and labeling

A.5.1 Forth-2012 systms

Section 5.1 defines the criteria that a system must meet in order to justify the label "Forth-2012 System". Briefly, the minimum requirement is that the system must "implement" the Core word set. There are several ways in which this requirement may be met. The most obvious is that all Core words may be in a pre-compiled kernel. This is not the only way of satisfying the requirement, however. For example, some words may be provided in source blocks or files with instructions explaining how to add them to the system if they are needed. So long as the words are provided in such a way that the user can obtain access to them with a clear and straightforward procedure, they may be considered to be present.A Forth cross compiler has many characteristics in common with a standard system, in that both use similar compiling tools to process a program. However, in order to fully specify a Forth-2012 standard cross compiler it would be necessary to address complex issues dealing with compilation and execution semantics in both host and target environments as well as ROMability issues. The level of effort to do this properly has proved to be impractical at this time. As a result, although it may be possible for a Forth cross compiler to correctly prepare a Forth-2012 standard program for execution in a target environment, it is inappropriate for a cross compiler to be labeled a Forth-2012 standard system.

A.5.2 Forth-2012 programs

A.5.2.2 Program labeling

Declaring an environmental dependency should not be considered undesirable, merely an acknowledgment that the author has taken advantage of some assumed architecture. For example, most computers in common use are based on two's complement binary arithmetic. By acknowledging an environmental dependency on this architecture, a programmer becomes entitled to use the number-1 to

represent all bits set without significantly restricting the

portability of the program.

Because all programs require space for data and instructions, and time to execute those instructions, they depend on the presence of an environment providing those resources. It is impossible to predict how little of some of these resources (e.g. stack space) might be necessary to perform some task, so this standard does not do so.

On the other hand, as a program requires increasing levels of resources, there will probably be sucessively fewer systems on which it will execute sucessfully. An algorithm requiring an array of 109 cells might run on fewer computers than one requiring only 103.

Since there is also no way of knowing what minimum level of resources will be implemented in a system useful for at least some tasks, any program performing real work labeled simply a "Standard Forth-2012 Program" is unlikely to be labeled correctly.

A.6 Glossary

In this and following sections we present rationales for the handling of specific words: why we included them, why we placed them in certain word sets, or why we specified their names or meaning as we did.Words in this section are organized by word set, retaining their index numbers for easy cross-referencing to the glossary.

Historically, many Forth systems have been written in Forth. Many of the words in Forth originally had as their primary purpose support of the Forth system itself. For example, WORD and FIND are often used as the principle instruments of the Forth text interpreter, and CREATE in many systems is the primitive for building dictionary entries. In defining words such as these in a standard way, we have endeavored not to do so in such a way as to preclude their use by implementors. One of the features of Forth that has endeared it to its users is that the same tools that are used to implement the system are available to the application programmer — a result of this approach is the compactness and efficiency that characterizes most Forth implementations.

Many Forth systems use a state-smart tick. Many do not. Forth-2012 follows the usage of Forth 94.

) ...

See: 6.2.0945 COMPILE,.

X ...

." ccc" ...

;

An implementation may define interpretation semantics for ." if desired. In one plausible implementation, interpreting ." would display the delimited message. In another plausible implementation, interpreting ." would compile code to display the message later. In still another plausible implementation, interpreting ." would be treated as an exception. Given this variation a Standard Program may not use ." while interpreting. Similarly, a Standard Program may not compile POSTPONE ." inside a new word, and then use that word while interpreting.

In Forth 83, this word was specified to alter the search order. This specification is explicitly removed in this standard. We believe that in most cases this has no effect; however, systems that allow many search orders found the Forth-83 behavior of colon very undesirable.

Note that colon does not itself invoke the compiler. Colon sets compilation state so that later words in the parse area are compiled.

One function performed by both ; and ;CODE is to allow the current definition to be found in the dictionary. If the current definition was created by :NONAME the current definition has no definition name and thus cannot be found in the dictionary. If :NONAME is implemented the Forth compiler must maintain enough information about the current definition to allow ; and ;CODE to determine whether or not any action must be taken to allow it to be found.

It is recommended that all non-graphic characters be reserved for editing or control functions and not be stored in the input string.

Because external system hardware and software may perform the ACCEPT function, when a line terminator is received the action of the cursor, and therefore the display, is implementation-defined. It is recommended that the cursor remain immediately following the entered text after a line terminator is received.

Reservation of data field space is typically done with ALLOT.

Typical use: ...

CREATE SOMETHING ...

X ... DOES> ... ;

Following DOES>, a Standard Program may not make any assumptions regarding the ability to find either the name of the definition containing the DOES> or any previous definition whose name may be concealed by it. DOES> effectively ends one definition and begins another as far as local variables and control-flow structures are concerned. The compilation behavior makes it clear that the user is not entitled to place DOES> inside any control-flow structures.

- Threaded code mechanisms.

These are the traditional approaches to implementing Forth,

but other techniques may be used.

- Subroutine threading with "macro-expansion" (code

copying). Short routines, like the code for DUP,

are copied into a definition rather than compiling a

JSRreference. - Native coding with optimization. This may include stack optimization (replacing such phrases as SWAP ROT + with one or two machine instructions, for example), parallelization (the trend in the newer RISC chips is to have several functional subunits which can execute in parallel), and so on.

The initial requirement (inherited from Forth 83) that compilation addresses be compiled into the dictionary disallowed type 2 and type 3 implementations.

Type 3 mechanisms and optimizations of type 2 implementations were hampered by the explicit specification of immediacy or non-immediacy of all standard words. POSTPONE allowed de-specification of immediacy or non-immediacy for all but a few Forth words whose behavior must be STATE-independent.

One type 3 implementation, Charles Moore's cmForth, has both compiling and interpreting versions of many Forth words. At the present, this appears to be a common approach for type 3 implementations. The committee felt that this implementation approach must be allowed. Consequently, it is possible that words without interpretation semantics can be found only during compilation, and other words may exist in two versions: a compiling version and an interpreting version. Hence the values returned by FIND may depend on STATE, and ' and ['] may be unable to find words without interpretation semantics.

The committee considered providing two complete sets of explicitly named division operators, and declined to do so on the grounds that this would unduly enlarge and complicate the standard. Instead, implementors may define the normal division words in terms of either FM/MOD or SM/REM providing they document their choice. People wishing to have explicitly named sets of operators are encouraged to do so. FM/MOD may be used, for example, to define:

NOT was originally provided in Forth as a

flag operator to make control structures readable. Under its

intended usage the following two definitions would produce

identical results:

This was common usage prior to the Forth-83 Standard which

redefined NOT as a cell-wide one's-complement

operation, functionally equivalent to the phrase -1

XOR. At the same time, the data type manipulated by

this word was changed from a flag to a cell-wide collection of

bits and the standard value for true was changed from "1"

(rightmost bit only set) to "-1" (all bits set). As these

definitions of TRUE and NOT were incompatible

with their previous definitions, many Forth users continue to

rely on the old definitions. Hence both versions are in common

use.

Therefore, usage of NOT cannot be standardized at

this time. The two traditional meanings of NOT —

that of negating the sense of a flag and that of doing a one's

complement operation — are made available by 0= and

INVERT, respectively.

See A.10.6.2.1305 EKEY.

: ENDIF

POSTPONE THEN

; IMMEDIATE

POSTPONE replaces most of the functionality of

COMPILE and [COMPILE]. COMPILE and

[COMPILE] are used for the same purpose: postpone the

compilation behavior of the next word in the parse area.

COMPILE was designed to be applied to non-immediate

words and [COMPILE] to immediate words. This burdens

the programmer with needing to know which words in a system

are immediate. Consequently, Forth standards have had to

specify the immediacy or non-immediacy of all words covered by

the standard. This unnecessarily constrains implementors.

A second problem with COMPILE is that some

programmers have come to expect and exploit a particular

implementation, namely:

: COMPILE R>

DUP @ , CELL+ >R

;

This implementation will not work on native code Forth systems.

In a native code Forth using inline code expansion and peephole

optimization, the size of the object code produced varies; this

information is difficult to communicate to a "dumb"

COMPILE. A "smart" (i.e., immediate) COMPILE

would not have this problem, but this was forbidden in previous

standards.

For these reasons, COMPILE has not been included in

the standard and [COMPILE] has been moved in favor of

POSTPONE. Additional discussion can be found in Hayes,

J.R., "Postpone", Proceedings of the 1989 Rochester

Forth Conference.

X ... RECURSE ... ;

This is Forth's recursion operator; in some implementations it

is called MYSELF. The usual example is the coding of

the factorial function.

n2 = n1(n1-1)(n1-2)...(2)(1), the product of n1 with all positive integers less than itself (as a special case, zero factorial equals one). While beloved of computer scientists, recursion makes unusually heavy use of both stacks and should therefore be used with caution. See alternate definition in A.6.1.2140 REPEAT.

STATE does not nest with text interpreter nesting. For example, the code sequence:

will leave the system in compilation state. Similarly, after LOADing a block containing ], the system will be in compilation state.

Note that ] does not affect the parse area and that the only effect that : has on the parse area is to parse a word. This entitles a program to use these words to set the state with known side-effects on the parse area. For example:

: NOP

: POSTPONE ; IMMEDIATE

;

Some non-compliant systems have ] invoke a

compiler loop in addition to setting STATE. Such a

system would inappropriately attempt to compile the second

use of NOP.

XYZ

A.7.2 Core extension words

The words in this collection fall into several categories:

- Words that are in common use but are deemed less essential than

Core words (e.g., 0<>);

- Words that are in common use but can be trivially defined from

Core words (e.g., FALSE);

- Words that are primarily useful in narrowly defined types of

applications or are in less frequent use (e.g., PARSE);

- Words that are being deprecated in favor of new words introduced to solve specific problems.

Because of the varied justifications for inclusion of these words, the committee does not encourage implementors to offer the complete collection, but to select those words deemed most valuable to their clientele.

)

However, many systems profit from a separation of uninitialized and initialized data areas. Such systems can implement BUFFER: so that it allocates memory from a separate uninitialized memory area. Embedded systems can take advantage of the lack of initialization of the memory area while hosted systems are permitted to ALLOCATE a buffer. A system may select a region of memory for performance reasons. A detailed knowledge of the memory allocation within the system is required to provide a version of BUFFER: that can take advantage of the system.

It should be noted that the memory buffer provided by BUFFER: is not initialized by the system and that if the application requires it to be initialized, it is the responsibility of the application to initialize it.

In traditional threaded-code implementations, compilation is performed by , (comma). This usage is not portable; it doesn't work for subroutine-threaded, native code, or relocatable implementations. Use of COMPILE, is portable.

In most systems it is possible to implement COMPILE, so it will generate code that is optimized to the same extent as code that is generated by the normal compilation process. However, in some implementations there are two different "tokens" corresponding to a particular definition name: the normal "execution token" that is used while interpreting or with EXECUTE, and another "compilation token" that is used while compiling. It is not always possible to obtain the compilation token from the execution token. In these implementations, COMPILE, might not generate code that is as efficient as normally compiled code.

The intention is that COMPILE, can be used as follows to write the classic interpreter/compiler loop:

Thus the interpretation semantics are left undefined, as COMPILE, will not be executed during interpretation.

The traditional Forth word for parsing is WORD. PARSE solves the following problems with WORD:

- WORD always skips leading delimiters. This

behavior is appropriate for use by the text interpreter,

which looks for sequences of non-blank characters, but is

inappropriate for use by words like ( , .(,

and .". Consider the following (flawed) definition

of .(:

: .( [CHAR]

)WORD COUNT TYPE ; IMMEDIATEThis works fine when used in a line like:

but consider what happens if the user enters an empty string:

The definition of .( shown above would treat the

)as a leading delimiter, skip it, and continue consuming characters until it located another)that followed a non-)character, or until the parse area was empty. In the example shown, the5. would be treated as part of the string to be printed.With PARSE, we could write a correct definition of .(:

: .( [CHAR]

)PARSE TYPE ; IMMEDIATEThis definition avoids the "empty string" anomaly.

- WORD returns its result as a counted string.

This has four bad effects:

- The characters accepted by WORD must be

copied from the input buffer into a transient buffer,

in order to make room for the count character that

must be at the beginning of the counted string. The

copy step is inefficient, compared to PARSE,

which leaves the string in the input buffer and doesn't

need to copy it anywhere.

- WORD must be careful not to store too many

characters into the transient buffer, thus overwriting

something beyond the end of the buffer. This adds to

the overhead of the copy step. (WORD may have

to scan a lot of characters before finding the trailing

delimiter.)

- The count character limits the length of the string

returned by WORD to 255 characters (longer

strings can easily be stored in blocks!). This

limitation does not exist for PARSE.

- The transient buffer is typically overwritten by the next use of WORD.

The need for WORD has largely been eliminated by PARSE and PARSE-NAME. WORD is retained for backward compatibility.

- The characters accepted by WORD must be

copied from the input buffer into a transient buffer,

in order to make room for the count character that

must be at the beginning of the counted string. The

copy step is inefficient, compared to PARSE,

which leaves the string in the input buffer and doesn't

need to copy it anywhere.

SAVE-INPUT and RESTORE-INPUT are intended for repositioning within a single input source; for example, the following scenario is NOT allowed for a Standard Program:

This is incorrect because, at the time RESTORE-INPUT is executed, the input source is the string via EVALUATE, which is not the same input source that was in effect when SAVE-INPUT was executed.

The following code is allowed:

After EVALUATE returns, the input source specification

is restored to its previous state, thus

SAVE-

INPUT

and RESTORE-INPUT are called with the same input source

in effect.

In the above examples, the EVALUATE phrase could have been replaced by a phrase involving INCLUDE-FILE and the same rules would apply.

The standard does not specify what happens if a program violates the above rules. A Standard System might check for the violation and return an exception indication from RESTORE-INPUT, or it might fail in an unpredictable way.

The return value from RESTORE-INPUT is primarily intended to report the case where the program attempts to restore the position of an input source whose position cannot be restored. The keyboard might be such an input source.

Nesting of SAVE-INPUT and RESTORE-INPUT is allowed. For example, the following situation works as expected:

In principle, RESTORE-INPUT could be implemented to "always fail", e.g.:

Such an implementation would not be useful in most cases. It would be preferable for a system to leave SAVE-INPUT and RESTORE-INPUT undefined, rather than to create a useless implementation. In the absence of the words, the application programmer could choose whether or not to create "dummy" implementations or to work-around the problem in some other way.

Examples of how an implementation might use the return values from SAVE-INPUT to accomplish the save/restore function:

| Input Source | possible stack values | |||

| block | >IN @ | BLK @ | 2 | |

| EVALUATE | >IN @ | 1 | ||

| keyboard | >IN @ | 1 | ||

| text file | >IN @ | lo-pos | hi-pos | 3 |

These are examples only; a Standard Program may not assume any particular meaning for the individual stack items returned by SAVE-INPUT.

x TO name

Some implementations of TO do not parse; instead they set a mode flag that is tested by the subsequent execution of name. Standard programs must use TO as if it parses. Therefore TO and name must be contiguous and on the same line in the source text.

0 0=.

33000 32000 34000 WITHIN

The above implementation returns false for that test, even though the unsigned number 33000 is clearly within the range {{32000 ... 34000}}.

The problem is that, in the incorrect implementation, the signed comparison < gives the wrong answer when 32000 is compared to 33000, because when those numbers are treated as signed numbers, 33000 is treated as negative 32536, while 32000 remains positive.

Replacing < with U< in the above implementation makes it work with unsigned numbers, but causes problems with certain signed number ranges; in particular, the test:

For two's-complement machines that ignore arithmetic overflow (most machines), the following implementation works in all cases:

A.9 The optional Block word set

Early Forth systems ran without a host OS; these are known as native systems. Such systems provide mass storage in blocks of 1024 bytes. The Block Word set includes the most common words for accessing program source and data on disk.

A.9.2 Additional terms

- block

- Forth systems may use blocks to contain program source. Conventionally such blocks are formatted for editing as 16 lines of 64 characters. Source blocks are often referred to as "screens".

A.9.3 Additional usage requirements

A.9.3.2 Block buffer regions

While the standard does not address multitasking per se, the items listed in 7.3.2 Block buffer regions that may render block-buffer addresses invalid are due to multitasking considerations. The standard restricts programs such that items that could fail on multitasking systems are not standard usage. It also permits multitasking systems to be declared standard systems.

A.9.6 Glossary

A.11 The optional Double-Number word set

Forth systems on 8-bit and 16-bit processors often find it necessary to deal with double-length numbers. But many Forths on small embedded systems do not, and many users of Forth on systems with a cell size of 32-bits or more find that the necessity for double-length numbers is much diminished. Therefore, we have factored the words that manipulate double-length entities into this optional word set.

Please note that the naming convention used in this word set conveys some important information:

-

Words whose names are of the form

2xxx deal with cell pairs, where the relationship between the cells is unspecified. They may be two-vectors, double-length numbers, or any pair of cells that it is convenient to manipulate together. -

Words with names of the form

Dxxx deal specifically with double-length integers. -

Words with names of the form

Mxxx deal with some combination of single and double integers. The order in which these appear on the stack is determined by long-standing common practice.

Refer to A.3.1 for a discussion of data types in Forth.

A.11.6 Glossary

x1 x2 2CONSTANT name

A.13 The optional Exception word set

CATCH and THROW provide a reliable mechanism for

handling exceptions, without having to propagate exception flags

through multiple levels of word nesting. It is similar in spirit

to the "non-local return" mechanisms of many other languages,

such as C's setjmp() and longjmp(), and LISP's

CATCH and THROW. In the Forth context, THROW

may be described as a "multi-level EXIT", with

CATCH marking a location to which a THROW may return.

Several similar Forth "multi-level EXIT" exception-handling schemes have been described and used in past years. It is not possible to implement such a scheme using only standard words (other than CATCH and THROW), because there is no portable way to "unwind" the return stack to a predetermined place.

THROW also provides a convenient implementation technique for the standard words ABORT and ABORT", allowing an application to define, through the use of CATCH, the behavior in the event of a system ABORT.

CATCH and THROW provide a convenient way for an implementation to "clean up" the state of open files if an exception occurs during the text interpretation of a file with INCLUDE-FILE. The implementation of INCLUDE-FILE may guard (with CATCH) the word that performs the text interpretation, and if CATCH returns an exception code, the file may be closed and the exception reTHROWn so that the files being included at an outer nesting level may be closed also. Note that the standard allows, but does not require, INCLUDE-FILE to close its open files if an exception occurs. However, it does require INCLUDE-FILE to unnest the input source specification if an exception is THROWn.

A.13.3 Additional usage requirements

One important use of an exception handler is to maintain program control under many conditions which ABORT. This is practicable only if a range of codes is reserved. Note that an application may overload many standard words in such a way as to THROW ambiguous conditions not normally THROWn by a particular system.

A.13.3.6 Exception handling

The method of accomplishing this coupling is implementation dependent. For example, LOAD could "know" about CATCH and THROW (by using CATCH itself, for example), or CATCH and THROW could "know" about LOAD (by maintaining input source nesting information in a data structure known to THROW, for example). Under these circumstances it is not possible for a Standard Program to define words such as LOAD in a completely portable way.

A.13.6 Glossary

Typical use:

KEY DUP [CHAR] Q = IF 1 THROW THEN ;

: do-it ( a b -- c) 2DROP could-fail ;

: try-it ( --)

1 2 ['] do-it CATCH IF

( x1 x2 ) 2DROP

." There was an exception" CR

ELSE

." The character was " EMIT CR

THEN

;

; retry-it ( -- )

BEGIN 1 2 ['] do-it CATCH

WHILE

( x1 x2) 2DROP

." Exception, keep trying" CR

REPEAT ( char )

." The character was " EMIT CR

;

A.15 The optional Facility word set

A.15.6 Glossary

Use of KEY or KEY? indicates that the application does not wish to process non-character events, so they are discarded, in anticipation of eventually receiving a valid character. Applications wishing to handle non-character events must use EKEY and EKEY?. It is possible to mix uses of KEY?/KEY and EKEY?/EKEY within a single application, but the application must use KEY? and KEY only when it wishes to discard non-character events until a valid character is received.

FIELD: definition.

While the name first school would define the same data structure as:

Although many systems provide a name first structure there is no common practice to the words used. The words BEGIN-STRUCTURE and END-STRUCTURE have been defied as a means of providing a portable notation that does not conflict with existing systems.

The field defining words (xFIELD: and

+FIELD) are defined so they can be used by both

schools. Compatibility between the two schools comes from

defining a new stack item struct-sys, which is

implementation dependent and can be 0 or more cells.

The name first school would provide an address (addr)

as the struct-sys parameter, while the name last

school would defined struct-sys as being empty.

Executing the name of the data structure, returns the size of the data structure. This allows the data stricture to be used within another data structure:

- For collecting related internal-use data into a

convenient "package" that can be referred to by a

single "handle". For this use, alignment is important,

so that efficient native fetch and store instructions

can be used.

- For mapping external data structures like hardware register maps and protocol packets. For this use, automatic alignment is inappropriate, because the alignment of the external data structure often doesn't match the rules for a given processor.

Many languages cater for the first use, but ignore the

second. This leads to various customized solutions, usage

requirements, portability problems, bugs, etc.

+FIELD is defined to be non-aligning, while the

named field defining words (xFIELD:) are

aligning. This is intentional and allows for both uses.

The standard currently defines an aligned field defining word for each of the standard data types:

| CFIELD: | a character |

| FIELD: | a native integer (single cell) |

| FFIELD: | a native float |

| SFFIELD: | a 32 bit float |

| DFFIELD: | a 64 bit float |

Although this is a sufficient set, most systems provide facilities to define field defining words for standard data types.

BFIELD: | 1 byte (8 bit) field |

WFIELD: | 16 bit field |

LFIELD: | 32 bit field |

XFIELD: | 64 bit field |

EKEY and EKEY? are implementation specific; no assumption can be made regarding the interaction between the pairs EKEY/EKEY? and KEY/KEY?. This standard does not define a timing relationship between KEY? and EKEY?. Undefined results may be avoided by using only one pairing of KEY/ KEY? or EKEY/EKEY? in a program for each input stream.

EKEY assumes no particular numerical correspondence between particular event code values and the values representing standard characters. On some systems, this may allow two separate keys that correspond to the same standard character to be distinguished from one another. A standard program may only interpret the results of EKEY via the translation words provided for that purpose (EKEY>CHAR and EKEY>FKEY).

See: A.6.1.1750 KEY, 10.6.2.1306 EKEY>CHAR and 10.6.2.1306.40 EKEY>FKEY.

It is possible that several different keyboard events may correspond to the same character, and other keyboard events may correspond to no character.

Typical Use:

CASE

K-UP OF ... ENDOF

K-F1 OF ... ENDOF

K-LEFT K-SHIFT-MASK OR K-CTRL-MASK OR OF ... ENDOF

...

ENDCASE

ELSE

...

THEN

The codes for the special keys are system-dependent, but this standard provides words for getting the key codes for a number of keys:

| Word | Key | Word | Key | |

| K-F1 | F1 | K-LEFT | cursor left | |

| K-F2 | F2 | K-RIGHT | cursor right | |

| K-F3 | F3 | K-UP | cursor up | |

| K-F4 | F4 | K-DOWN | cursor down | |

| K-F5 | F5 | K-HOME | home or Pos1 | |

| K-F6 | F6 | K-END | End | |

| K-F7 | F7 | K-PRIOR | PgUp or Prior | |

| K-F8 | F8 | K-NEXT | PgDn or Next | |

| K-F9 | F9 | K-INSERT | Insert | |

| K-F10 | F10 | K-DELETE | Delete | |

| K-F11 | F11 | |||

| K-F12 | F12 | |||

In addition, you can get codes for shifted variants of these keys by ORing with K-SHIFT-MASK, K-CTRL-MASK and/or K-ALT-MASK, e.g. K-CTRL-MASK K-ALT-MASK OR K-DELETE OR. The masks for the shift keys are:

| Word | Key |

| K-SHIFT-MASK | Shift |

| K-CTRL-MASK | Ctrl |

| K-ALT-MASK | Alt |

Note that not all of these keys are available on all systems, and not all combinations of keys and shift keys are available. Therefore programs should be written such that they continue to work (although less conveniently or with less functionality) if these key combinations cannot be produced.

The various xFIELD: words provide for different

alignment and size allocation.

The xFIELD: words could be defined as:

: CFIELD: ( n1 "name" -- n2 ; addr1 -- addr2 ) 1 CHARS +FIELD ;

: FFIELD: ( n1 "name" -- n2 ; addr1 -- addr2 ) FALIGNED 1 FLOATS +FIELD ;

: SFFIELD: ( n1 "name" -- n2 ; addr1 -- addr2 ) SFALIGNED 1 SFLOATS +FIELD ;

: DFFIELD: ( n1 "name" -- n2 ; addr1 -- addr2 ) DFALIGNED 1 DFLOATS +FIELD ;

A.17 The optional File-Access word set

A.17.3 Additional usage requirements

A.17.3.2 Blocks in files

Many systems reuse file identifiers; when a file is closed, a subsequently opened file may be given the same identifier. If the original file has blocks still in block buffers, these will be incorrectly associated with the newly opened file with disastrous results. The block buffer system must be flushed to avoid this.

A.17.3.4 Other transient regions

Additional transient buffers are provided for use by S" and S\". The buffers should be able to store two consecutive strings, thus allowing the command line:

S" name1" S" name2" RENAME-FILE

The buffers may be implemented in a circular arrangement, where a string is placed into the next available buffer. When there are no buffers available, the oldest buffer is overwritten.

S" and S\" may share the same buffers.

The list of words using memory in transient regions is extended to include 11.6.1.2165 S" and 11.6.2.2266 S\". See 3.3.3.6 Other transient regions.

A.17.6 Glossary

The arguments to READ-FILE and WRITE-FILE are arrays of character storage elements, each element consisting of at least 8 bits. The committee intends that, in BIN mode, the contents of these storage elements can be written to a file and later read back without alteration.

- Save the file position (as returned by

FILE-POSITION) of the beginning of the line being

interpreted. To restore the input source specification,

seek to that position and re-read the line into the input

buffer.

- Allocate a separate line buffer for each active text input file, using that buffer as the input buffer. This method avoids the "seek and reread" step, and allows the use of "pseudo-files" such as pipes and other sequential-access-only communication channels.

filename" INCLUDED ...

Standard Programs may not depend on the presence of any such terminator sequence in the buffer.

A typical line-oriented sequential file-processing algorithm might look like:

READ-LINE needs a separate end-of-file flag because empty (zero-length) lines are a routine occurrence, so a zero-length line cannot be used to signify end-of-file.

" ...

The interpretation semantics for S" are intended to provide a simple mechanism for entering a string in the interpretation state. Since an implementation may choose to provide only one buffer for interpreted strings, an interpreted string is subject to being overwritten by the next execution of S" in interpretation state. It is intended that no standard words other than S" should in themselves cause the interpreted string to be overwritten. However, since words such as EVALUATE, LOAD, INCLUDE-FILE and INCLUDED can result in the interpretation of arbitrary text, possibly including instances of S", the interpreted string may be invalidated by some uses of these words.

When the possibility of overwriting a string can arise, it is prudent to copy the string to a "safe" buffer allocated by the application.

filename

filename

filename" REQUIRED

A.19 The optional Floating-Point word set

The current base for floating-point input must be DECIMAL.

Floating-point input is not allowed in an arbitrary base. All

floating-point numbers to

be interpreted by a standard system must contain the exponent

indicator "E" (see 12.3.7 Text interpreter input number conversion). Consensus in the committee deemed

this form of floating-point input to be in more common use than

the alternative that would have a floating-point input mode that

would allow numbers with embedded decimal points to be treated

as floating-point numbers.

Although the format and precision of the significand and the format and range of the exponent of a floating-point number are implementation defined in Forth-2012, the Floating-Point Extensions word set contains the words DF@, SF@, DF!, and SF! for fetching and storing double- and single-precision IEEE floating-point-format numbers to memory. The IEEE floating-point format is commonly used by numeric math co-processors and for exchange of floating-point data between programs and systems.

A.19.3 Additional usage requirements

A.19.3.5 Address alignment

In defining custom floating-point data structures, be aware that CREATE doesn't necessarily leave the data space pointer aligned for various floating-point data types. Programs may comply with the requirement for the various kinds of floating-point alignment by specifying the appropriate alignment both at compile-time and execution time. For example:

A.19.3.7 Text interpreter input number conversion

The committee has more than once received the suggestion that the text interpreter in standard Forth systems should treat numbers that have an embedded decimal point, but no exponent, as floating-point numbers rather than double cell numbers. This suggestion, although it has merit, has always been voted down because it would break too much existing code; many existing implementations put the full digit string on the stack as a double number and use other means to inform the application of the location of the decimal point.

A.19.6 Glossary

This is a synthesis of common FORTRAN practice. Embedded spaces are explicitly forbidden in much scientific usage, as are other field separators such as comma or slash.

While >FLOAT is not required to treat a string of blanks as zero, this behavior is strongly encouraged, since a future version of this standard may include such a requirement.

r FCONSTANT name

1E3 F. displays 1000.

FSINCOS returns a Cartesian unit vector in the direction of the given angle, measured counter-clockwise from the positive X-axis. The order of results on the stack, namely y underneath x, permits the 2-vector data type to be additionally viewed and used as a ratio approximating the tangent of the angle. Thus the phrase FSINCOS F/ is functionally equivalent to FTAN, but is useful over only a limited and discontinuous range of angles, whereas FSINCOS and FATAN2 are useful for all angles.

The argument order for FATAN2 is the same, converting a vector in the conventional representation to a scalar angle. Thus, for all angles, FSINCOS FATAN2 is an identity within the accuracy of the arithmetic and the argument range of FSINCOS. Note that while FSINCOS always returns a valid unit vector, FATAN2 will accept any non-null vector. An ambiguous condition exists if the vector argument to FATAN2 has zero magnitude.

An important application of this word is in finance; say a loan is repaid at 15% per year; what is the daily rate? On a computer with single-precision (six decimal digit) accuracy:

- Using FLN and FEXP:

FLN of 1.15 = 0.139762,

divide by 365 = 3.82910E-4,

form the exponent using FEXP = 1.00038, and

subtract one (1) and convert to percentage = 0.038%.

- Using FLNP1 and FEXPM1:

FLNP1 of 0.15 = 0.139762, (this is the same value

as in the first example, although with the argument closer

to zero it may not be so)

divide by 365 = 3.82910E-4,

form the exponent and subtract one (1) using FEXPM1 = 3.82983E-4, and

convert to percentage = 0.0382983%.

A.21 The optional Locals word set

A.21.3 Additional usage requirements

Rule 13.3.3.2d could be relaxed without affecting the integrity of the rest of this structure. 13.3.3.2c could not be.13.3.3.2b forbids the use of the data stack for local storage because no usage rules have been articulated for programmer users in such a case. Of course, if the data stack is somehow employed in such a way that there are no usage rules, then the locals are invisible to the programmer, are logically not on the stack, and the implementation conforms.

Access to previously declared local variables is prohibited by Section 13.3.3.2d until any data placed onto the return stack by the application has been removed, due to the possible use of the return stack for storage of locals.

Authorization for a Standard Program to manipulate the return stack (e.g., via >R R>) while local variables are active overly constrains implementation possibilities. The consensus of users of locals was that Local facilities represent an effective functional replacement for return stack manipulation, and restriction of standard usage to only one method was reasonable.

Access to Locals within DO...LOOPs is expressly permitted as an additional requirement of conforming systems by Section 13.3.3.2g. Although words, such as (LOCAL), written by a System Implementor, may require inside knowledge of the internal structure of the return stack, such knowledge is not required of a user of compliant Forth systems.

A.21.6 Glossary

Since then, common practice has emerged. Most implementations that

provide (LOCAL) and LOCALS| also provide some form of the

{ ... } notation; however, the phrase { ... } conflicts with

other systems. The {: ... :} notation is a compromise

to avoid name conflicts.

The notation provides for different kinds of local: those that are

initialized from the data stack at run-time, uninitialized locals, and

outputs. Initialized locals are separated from uninitialized locals by

`|'. The definition of locals is terminated by

`--' or `:}'.

All text between `--' and `:}' is ignored. This eases

documentation by allowing a complete stack comment in the locals definition.

The `|' (ASCII $7C) character is widely used as the

separator between local arguments and local values. Some implementations

have used `\' (ASCII $5C) or `¦' ($A6).